THE SIGNPOST 1902-3 and 1947-8 CONNECTION IN ‘O, JERUSALEM.’

One indispensable textbook that catalogues the events of the formation of the State of Israel is the classic ‘O, Jerusalem’ by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre. The 650-page book took five years of careful research and is also based on thousands of interviews. In the opening pages the authors manage to overview the history of the Hebrew people both ancient and in the modern era that culminated in the 1948 War of Independence.

The importance of this following extract, and the rest of their book, cannot be overstated. The writers tie together the long Jewish Diaspora and their centuries of dreams for a reinstatement to their former holy Land and Capital City Jerusalem, with the coming of Herzl and his facilitation under the auspices of the Zionism he founded, for that return ‘starting just after the turn of the 20th century.’ This is, as we will show, exactly in line with the first Signpost Year 1902.

“In the afternoon of Saturday November 29th 1947, in a cavernous gray building that had once housed an ice-skating rink, in Flushing Meadow, New York, the delegates of fifty-six of the fifty-seven members of the General Assembly of the United Nations were called upon to decide the future of a sliver of land set on the eastern rim of the Mediterranean. Half the size of Denmark, harbouring fewer people than the city of St Louis, it had been the center of the universe for the cartographers of antiquity, the destination of all he roads of man when the world was young: Palestine.

No debate in the brief history of the United Nations had stirred passions comparable to those aroused by the controversy over that land to which each of its members might in some way trace part of its spiritual heritage. Before the General Assembly was a proposal to cut the ancient territory into two separate states, one Arab, one Jewish. The proposal represented the collective wisdom of a United Nations special committee instructed to find some way of resolving thirty years of struggle between Jew and Arab for the control of Palestine.

A mapmaker’s nightmare, it was, at best, a possible compromise; at worse, an abomination. It gave fifty-seven percent of Palestine to the Jewish people despite the fact that two-thirds of its population and more than half of its land was Arab. The Arabs owned more land in the Jewish state than the Jews did, and before immigration that state would contain a majority of barely a thousand Jews. Each state was split into three parts linked up by a series of international crossroads upon whose functioning the whole scheme depended. Both states were militarily indefensible.

Most important, the United Nations plan refused to both states sovereignty over the city of Jerusalem, the pole to which, since antiquity, the political, economic and religious life of Palestine had gravitated. Holding the attachment to Jerusalem too widely spread and deeply felt, its potential for promoting strife too great to entrust it to one nation’s care, the United Nations Special Committee in Palestine had recommended that the city and its suburbs be placed under an international trusteeship.

The proposal had been a staggering blow to Jewish hopes. Re-creating a Jewish state in Palestine without Jerusalem as its capital was anathema to the Jewish people, the resurrection of a body without a soul.

Two thousand years of dispersion were summed up in the phrase, ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem (let my right hand wither, let my tongue cleave to my palate, if I do not remember you…).’ The most important wall of the synagogues of the Diaspora faced east to Jerusalem. A patch of wall in every Orthodox household went unattended in Jerusalem’s name. The Jewish bridegroom crushed a glass under his foot at his wedding to show his grief at the destruction of the Temple, and prayed that his marriage would provoke joy and dancing in the streets of Jerusalem. The traditional words of Jewish consolation, ‘May the Almighty comfort you and all the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem,’ evoked the City. Even the word ‘Zionism’, defining the movement to reassemble the Jews in their ancient homeland, was inspired by a hilltop in Jerusalem, Mount Zion.

Through the generations, men with neither the interest nor the intent – nor even the –remotest possibility – of ever gazing on Judea’s hills had nonetheless solemnly pledged to each other at the end of their Passover feast, ‘Next Year in Jerusalem. Beyond those spiritual concerns lay strategic ones. Two out of every three inhabitants of Jerusalem were Jewish. They represented almost one-sixth of the entire Jewish settlement in Palestine. With Jerusalem and a wide access corridor to the sea, the Jewish state would have a firm foothold in the Judean heartland of Palestine. Without it, the state risked becoming a coastal enclave clinging to the Mediterranean.

Urged by the Vatican, the Catholic nations of Latin America had made it clear to the Jews that the price of their votes for the plan to partition Palestine would be the internationalization of Jerusalem. Without them, the Jews had no hopes of mustering the ballots needed to pass partition. With a heavy heart, they had yielded, and Jerusalem’s loss was the measure of the price they were willing to pay for a Jewish state.

Despite the loss of Jerusalem, the partition plan proposed by the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine still promised the Jewish people – and, above all, the 60,000 Jews of Palestine – the fulfillment of a two-thousand-year-old dream and urgent present need. With a constancy, a tenacity, unequaled in the annals of mankind, the Jews had clung to the memory of the Biblical kingdom from which they had been driven in AD 70 as the centuries of their dispersion had stretched towards an eternity. In their prayers, in their rites, at each salient moment in the passage of a lifetime, they had reminded themselves of their attachment to that Promised Land and the transient nature of their separation from its shores.

Their ancestors, the first wandering Hebrew tribes fleeing Mesopotainia, had barely set foot on that land before history condemned them to ten centuries of warfare, migration and slavery. Finally, fleeing Egypt under Moses, they began their forty-year trek back to the hills of Judea to found their first sovereign state.Its apogee, under David and Solomon, lasted barely a century. Living at the crossroads of the caravan routes of Europe, Asia and Africa, installed on a land that was already a beckoning temptation to every nearby civilization, the Hebrews endured a millennium of unremitting assaults. Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, Rome, each one in turn sent its cohorts to conquer their land. Twice, in 586 BC and in AD 70, their conquerors inflicted upon them the supreme ordeal of exile and destroyed the Temple they had built in Jerusalem’s Mount Moriah to Yahweh (Jehovah), their one and universal deity. From those dispersions and the sufferings accompanying them was born their tenacious attachment to their ancient land.

Reinforcing its appeal, giving it a continual contemporary urgency, was the curse of persecution which had followed the Jews into every haven in which they had taken shelter during their dispersal. The roots of Jewish suffering grew out of the rise of another religion dedicated, paradoxically, to the love of man for man. Burning in the ardour of their new faith to convert the pagan masses, the early fathers of the Christian Church strove to emphasize the differences between their religion and its theological predecessor by forcing upon the Jews a kind of spiritual apartheid. The Emperor Theodosius II gave those aspirations legal force in his code, condemning Judaism and, for the first time, legally branding the Jews a people apart.

Dagobert, King of the Franks, drove them from Gaul; Spain’s Visigoths seized their children as converts; the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius forbade Jewish worship. With the Crusades, spiritual apartheid became systematic slaughter. Shrieking their cry ‘Deus vult! God wills it!’ the Crusaders fell on every hapless Jewish community on their route to Jerusalem.

Most countries barred Jews from owning land. The religiously organized medieval craft and commerce guilds were closed to them. The Church forbade Jews to employ Christians and Christians lived among Jews. Most loathsome of all was the decision of the Forth Lateran Council in 1215 to stamp the Jews a race apart by forcing them to wear a distinguishing badge. In England it was a replica of the tablets on which Moses received the Ten Commandments. In France and Germany it was a yellow O, forerunner of the yellow stars with which the Third Reich would one day mark the victims of its gas chambers.

Edward I of England and later Philip the Fair of France expelled Jews from their nations, seizing their property before evicting them. Even the Black Death was blamed on the Jews, accused of poisoning Christian wells with a powder made of spiders, frogs’ legs, Christian entrails and consecrated hosts. Over two hundred Jewish communities were exterminated in the slaughters stirred by that wild frenzy.

During those dark centuries, the only example of normal Jewish existence in the West was in the Spain of the Caliphate, where, under Arab rule, the Jewish people flourished as they never would again in the Diaspora. The Christian Reconquista ended that. In 1492 Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the Jews from Spain.

In Germany, Jews were forbidden to ride in carriages and were made to pay a special toll as they entered a city. The republic of Venice enriched the vocabulary of the world with the term ghetto from the quarter, Ghetto Nuovo - New Foundry - to which the republic restricted Jews.In Poland, the Cossack Revolt, with a ferocity and devotion to torture unparalleled in Jewish experience, wiped out over 100,000 Jews in less than a decade. When the czars pushed their frontier westwards across Poland, an era of darkness set in for almost half the world’s Jewish population. Fenced into history’s greatest ghetto, The Pale of Settlement, Jews were conscripted at the age of twelve for twenty-five years of military service and forced to pay special taxes on kosher meat and Sabbath candles. Jewish women were not allowed to live in the big city university centers without the yellow ticket of a prostitute. In 1880, after the assassination of Alexander II, the mobs, aided by the Czar’s soldiers, burned and butchered their way through one Jewish community after another, leaving a new word in their wake: pogrom.

Bloody milestones on the road to Hitler’s gas chambers, those slaughters succeeding one another through the centuries were the constant of Jewish history, the ghastly heritage of an oppressed race to whom the crematoriums of the Third Reich might seem only the final, most appalling manifestation of their destiny.Yet, by a strange paradox, the event which produced the decisive Jewish reaction to that bloodstained history was not a pogrom, not a slaughter, nor a Cossack troop’s brutality. It was a military ceremony, a ritual whose killing was spiritual, the public humiliation of Captain Alfred Dreyfus in Paris in January 1895.

In the midst of the crowd massed on the esplanade of the Champs de Mars to watch the ceremony was a Viennese newspaperman named Theodor Herzl. Like Dreyfus, Herzl was a Jew. Like Dreyfus, he had left his life in comfortable, seemingly unassailable assimilation into European society little concerned with his race or religion. Suddenly, on that windy esplanade, Herzl heard the mob around him beginning to cry, ‘Kill the traitor! Kill the Jew!’ A shock wave rolled through his being. He had understood. It was not just for the blood of Alfred Dreyfus that the crowd was clamouring: it was for his blood, for Jewish blood. Herzl walked away from that spectacle a shattered man: but from his anguish came a vision that modified the destiny of his people and the history of the twentieth century. It was Zionism. With the energy of his despair, Herzl produced its blue-print, a one-hundred-page pamphlet titled Der Judenstaat – ‘The Jewish State.’ ‘The Jews who will it,’ it began, ‘shall have a state of their own.’

Two years later, Herzl formally launched his movement with the First World Zionist Congress in the gambling casino of Basle, Switzerland. The delegates of Herzl’s congress elected an international Jewish executive to guide the movement, created a Jewish National Fund and a Land Bank to begin buying land in the area in which he hoped to create his state, Palestine.

They picked two indispensable symbols of the state whose foremost claim to existence was in the fervour of their speeches, a flag and a national anthem.

The flag was white and blue for the colours of the tallith, the shawl worn by Jews at prayer. The title of the Hebrew song chosen as a national anthem was even more appropriate. It represented the one asset Herzl and his followers disposed of in abundance. It was ‘Hatikvah’ – ‘The Hope.’

At no time had Jewish life wholly disappeared in the Palestine to which Herzl’s followers proposed to return. Even in the darkest hours of the dispersion, small colonies of Jews had survived in Safed, Tiberias and Galilee. As elsewhere, their cruellest sufferings had come under Christian rule. The early Christians had banned them from Jerusalem, and the Crusaders burned the Holy City’s Jews alive in their synagogues.

Palestine’s Moslem rulers had been more tolerant. The Caliph Omar had left them relatively unmolested. Saladin had brought them back to Jerusalem along with his Moslem faithful; under the Ottoman Turks, they had been able to take the first steps towards a return to the Promised Land. Sir Moses Montefiore, an English philanthropist, built the first Jewish suburb outside Jerusalem’s old walls in 1860, offering his kinsmen a pound sterling to spend a night beyond its

ramparts. By the winter day in 1895 when Theodor Herzl witnessed the degradation of Alfred Dreyfus, thirty thousand of Jerusalem’s fifty thousand inhabitants were already Jewish.

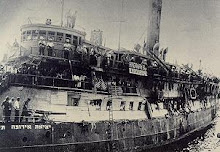

A series of pogroms in Russia just after the turn of the century sent a new shock wave of immigrants to Palestine. They represented the fruit of Herzl’s movement. Practical idealists, those immigrants were Zionism’s first pioneers, and from their ranks would come half a century of leadership for the movement.”

(The authors go on at this point to list some of those early pioneers, such as David Ben-Gurion)

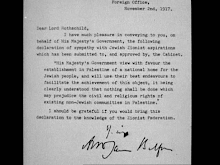

In line with The Signpost Years, Collins and Lapierre, writing nearly forty years ago, identified the direct causal link between the beginning of the first Zionist migrations specifically facilitated by the intentions of Herzl’s new movement ‘starting at the turn of the 20th Century’ and the later founding of the State of Israel at the further Signpost epoch of 1947-8.

Indeed, the four-year ‘series of pogroms and shock-wave reaction’ to which they also link the Zionist immigration account are, to put a number on it, regarded by some modern historians of Israel as having started in Czestochowa, and 50 miles away at Bialystok, precisely in 1902, culminating in the horror that was Kishinev in 1903.

We have added to this, elsewhere, the eyewitness testimony of Jewish historian Max Nordau who pinpoints this exact same time-milestone, 1901-3, as also signaling the first Constituted and functional emergence of World Zionist Organization.

Again and again, these notes make the point that we do not have to look far or deep to spot writers, historians, politicians and journalists, old and modern, unwittingly and with ‘double-blind’ accuracy, singling out those events and critical historical turning points that converge directly with the Clarke and Guinness Biblical Signpost Years, foretold by both scholars decades in advance.

Reference:

‘O, Jerusalem.’ Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre. (1972) Published by Granada Publishing, 1982. ISBN 0 586 05452 9. (pp 3 – 8)

Also, see Psalm 137 verses 4 to 6.

(9sep)

Introduction

ONE HUNDRED AND FORTY YEARS BEFORE the actual events came to fruition in the Middle East, two dedicated Bible scholars predicted accurately several key years in the then approaching conflict for tenure of the holy Land and Jerusalem, involving a long prophesised regathering of the Jews to their Promised Land, after nearly 2000 years of Diaspora.

Doctors Clarke and Guinness pointed well in advance to the coming years 1902, 1917, 1947-8 and 1967 AD, having based their predictions on the 2,500 year old Biblical book of Daniel.

Not only did their advance forecasts prove accurate decades later, but those key 'Signpost Years’ continue to mark events and developments in the holy Land, ever since their occurrence in modern times, that now represent the specific themes of serious contention in the struggle for Peace in that region today.

These following NOTES explain the rational behind the Clarke-Guinness thinking in as fast and concise a form as possible, and elaborations will follow. A second critical aim here is not to prove 'The Signpost Years' correct, but rather to use the scientific approach of attempting their falsification first. You can help either way by passing on any objective comments to this site.

PART 1 Is an Introduction and looks at each of the Signpost Years as they were foretold in the writings of Guinness and Clarke. It looks at many of the side issues and has a number of detailed footnotes.

PART 2 Looks at the period 1901 – 1903, and the first of the Signpost Years predicted by Clarke in 1825. This part explains the huge significance of the period and sets the scene for a further link that comes in Part 4.

PART 3 Begins to address some of the typical questions that might arise in the mind of the reader regarding the Signpost Years. Items are added to this from time to time as new considerations are brought to light. Again, feel free to contribute any comments that will add to those pages.

PART 4 Looks at the Signpost Years in the light of the last 6 months of Christ’s Ministry, and especially the last week of messages He imparted to His followers for the future. It ties directly back into PART 2.

*****************************************************

TO READ SPECIFIC 'CHAPTERS' CLICK ONE OF THE 'QUICK LINKS' LISTED DIRECTLY BELOW, AND TO READ OR ADD COMMENTS, CLICK 'POST COMMENT' AT THE END OF EACH CHAPTER THAT WILL OPEN AN EMAIL BOX TO SEND TO THIS BLOG.

AGAIN YOU CAN SIMPLY EMAIL TO:

karl@thesignpostyears.com

Click on QUICK LINKS to Parts 1 to 4 of the Signpost Notes:

Part 1: Introduction, Timelines, Conclusion.

Part 2: The SignPost Year 1902 AD and Max Nordau

Part 3: Q & A on the Signpost Years

Part 4: Jesus and the Signpost Years

Doctors Clarke and Guinness pointed well in advance to the coming years 1902, 1917, 1947-8 and 1967 AD, having based their predictions on the 2,500 year old Biblical book of Daniel.

Not only did their advance forecasts prove accurate decades later, but those key 'Signpost Years’ continue to mark events and developments in the holy Land, ever since their occurrence in modern times, that now represent the specific themes of serious contention in the struggle for Peace in that region today.

These following NOTES explain the rational behind the Clarke-Guinness thinking in as fast and concise a form as possible, and elaborations will follow. A second critical aim here is not to prove 'The Signpost Years' correct, but rather to use the scientific approach of attempting their falsification first. You can help either way by passing on any objective comments to this site.

PART 1 Is an Introduction and looks at each of the Signpost Years as they were foretold in the writings of Guinness and Clarke. It looks at many of the side issues and has a number of detailed footnotes.

PART 2 Looks at the period 1901 – 1903, and the first of the Signpost Years predicted by Clarke in 1825. This part explains the huge significance of the period and sets the scene for a further link that comes in Part 4.

PART 3 Begins to address some of the typical questions that might arise in the mind of the reader regarding the Signpost Years. Items are added to this from time to time as new considerations are brought to light. Again, feel free to contribute any comments that will add to those pages.

PART 4 Looks at the Signpost Years in the light of the last 6 months of Christ’s Ministry, and especially the last week of messages He imparted to His followers for the future. It ties directly back into PART 2.

*****************************************************

TO READ SPECIFIC 'CHAPTERS' CLICK ONE OF THE 'QUICK LINKS' LISTED DIRECTLY BELOW, AND TO READ OR ADD COMMENTS, CLICK 'POST COMMENT' AT THE END OF EACH CHAPTER THAT WILL OPEN AN EMAIL BOX TO SEND TO THIS BLOG.

AGAIN YOU CAN SIMPLY EMAIL TO:

karl@thesignpostyears.com

Click on QUICK LINKS to Parts 1 to 4 of the Signpost Notes:

Part 1: Introduction, Timelines, Conclusion.

Part 2: The SignPost Year 1902 AD and Max Nordau

Part 3: Q & A on the Signpost Years

Part 4: Jesus and the Signpost Years

The SignPost Years

Click on QUICK LINKS 1 to 3 here for Signpost Year Notes:

Part 1: Introduction, Timelines, Conclusion.

Part 2: The SignPost Year 1902 AD and Max Nordau

Part 3: Q & A on the Signpost Years

Part 4: Jesus and the Signpost Years

Part 1: Introduction, Timelines, Conclusion.

Part 2: The SignPost Year 1902 AD and Max Nordau

Part 3: Q & A on the Signpost Years

Part 4: Jesus and the Signpost Years